Richard Nixon was riding high by 1972 — an historic visit to China, an Anti-Ballistic Missile treaty with the Soviet Union, an end to the Vietnam War on the horizon, and a landslide victory over George McGovern in the presidential election. But appearances were deceiving. Despite manipulating public perceptions for decades, electability wasn’t enough. He was about to be exposed.

In June, operatives working for the Committee to Re-elect the President were caught during a break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in Washington’s Watergate office complex. Within hours one of the “masterminds,” G. Gordon Liddy, attempted to shred all related documents. Two days later, Nixon’s press secretary called it a “third rate burglary.” But the damage was done, and two years later Nixon resigned in disgrace.

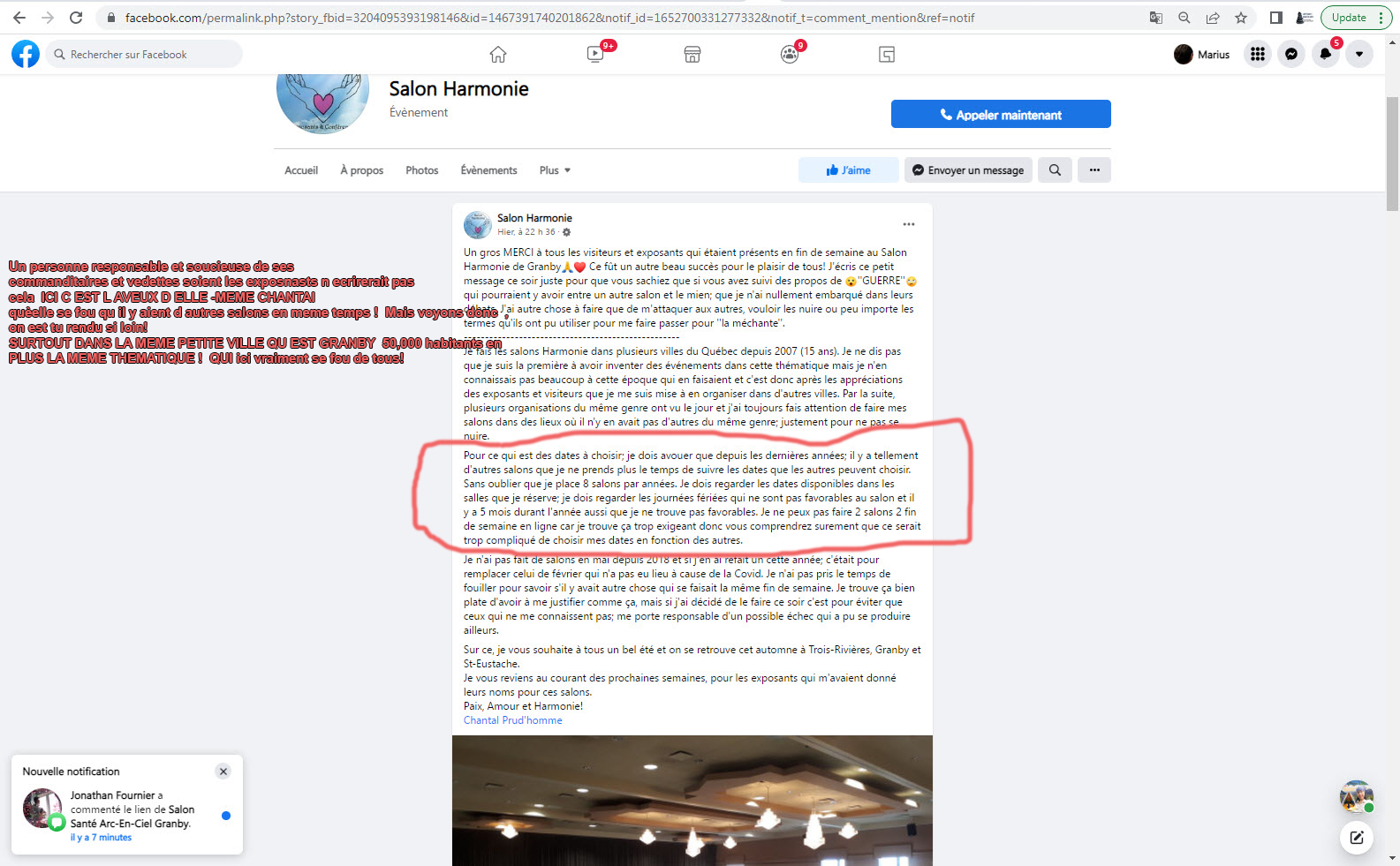

Image: Richard Nixon (Licensed under Creative Commons)

According to Douglas Hallett, a White House staff assistant to Charles Colson, the Watergate scandal “was an almost organic outgrowth of a White House peopled by competitive political animals who were rewarded in direct proportion to their expressions of fear, suspicion and paranoia.”

Hallett worked closely with Colson, who said that he would “walk over my grandmother” to assure Richard Nixon a second term as President. Hallett felt that Colson, a dirty tricks expert, “was a man without ethical compass; there was an absence of fixed direction and conviction. He was proud of having worked his way up from practically nothing, and regarded himself as the living embodiment of the American Dream.”

Hallett’s portrait of Nixon was chilling: “Awkward remarks popped up constantly like his ‘This is a great day for France’ comment at President Pompidou’s funeral or his ‘Do you like your job?’ question to a policeman who had suffered an accident during one of Nixon’s Florida campaign tours and was awaiting an ambulance.

“Once, a woodcarver was ushered into the Oval Office to present the President with a chair he had fashioned from a single piece of wood. When Nixon sat down in the chair, according to one of those present, it collapsed into pieces. Picking himself off the floor, the President asked, as if nothing had happened, ‘Well, how do you go about doing this kind of work?’ Most memorable of all, at least for me, was shaking hands with Nixon. Each time I did, I had the eerie, even frightening feeling that nobody was there; face-to-face, hands clasped, yet no feeling, no feeling at all.”

Staffed by ethically-challenged administrators, and led by a President who appeared drained of real emotion, the administration found coercive methods — a drive for negative power — the “rational” solution in a pervasive atmosphere of fear and suspicion. Nixon had been more than willing to make any sacrifices necessary to win the highest office in the land. In many ways he was a model of the “rational manager.” Dedicated to the practical, to the need for discipline and sacrifice, constantly monitoring and evaluating his own actions, and obsessed with his image, he was an “electronic messiah” who exploited mass media in a search for “greatness,” his euphemism for ever-escalating production and continued dissemination of the American Dream.

Nixon made frequent use of slogans — the silent majority, peace with honor — and key words. Three concepts were linked: greatness, sacrifice, and responsibility. During the Nixon era, mass consciousness was saturated with this formula for “the good life.” A “good” citizen begins by shouldering responsibility, welcoming, even thriving upon sacrifices, and finally, through effort, restraint and pain, attains material comfort and, potentially, greatness. Even after his political “assassination,” those remained American facts of life, the way of the electronic messiah.

.

.

After more than two decades in public life, Richard Nixon knew his audience well. Millions watched him on January 20, 1973 as he delivered a sermon he’d rehearsed for years. In his second inaugural address, he told the viewers (aka public) to push thoughts of “those who find everything wrong with America and very little right with it” out of their minds, to forget dissent and war in Vietnam. In short, he urged people to forget much of the recent past.

Instead, he recommended a different preoccupation — responsibility. Denying that each man is his brother’s keeper, he appealed to individualism: “Let each of us ask not just what government can do for me, but what can I do for myself?” Concern for others was a manifestation of the “condescending policies of paternalism,” he argued. The goal was to become elite competitors.

In a letter to his wife, Gordon Liddy explained:

“The young should be raised in harmony with nature. Nature is elitist. By definition, not everyone can be a member of an elite – but it is of the nature of men to try.”

By the time the Senate formed a committee to investigate the Watergate burglary, democratization of Nixonian ethics was well advanced. “Law and order” was consistent with previous assertions. But democratization of values is usually accompanied by the rejection of the monarch. Thus, this would-be king began to face resistance. Impoundment of federal funds led to work stoppages, government reorganization produced instability, and central leadership through information control threatened anonymity. Such developments conflicted with fundamental laws of government and media bureaucracies.

The US looked in some ways as if it was replicating the political degradation of Rome. In 44 BC, having crossed the Rubicon and routed Pompey, Julius Caesar became dictator of the world’s most powerful empire. Although the new monarch effected a reorganization of local administration, his “vulgar scheming for the tawdriest mockeries of personal worship,” as H.G. Wells put it, became a silly and shameful record of his rule. The air buzzed with talk of the Senate, democracy, and the proletariat. The popular “comitia,” the gathering of tribes for public votes, didn’t often reflect the feelings of the masses. Elite clubs were joined by most eligible voters. Politicians depended upon usurers and the clubs. The sham of democracy forced the cheated and suppressed to use other methods of expression: strikes and insurrection.

Caesar’s rule lasted only about four years — less even than Nixon’s — and ended in assassination by his “friends” and supporters when his aspirations to power and greatness became intolerable. In Wells’ words, he was “beset in the senate….the scene marks the complete demoralization of the old Roman governing body.” The fall of this dictator, about 2000 years prior to Nixon’s resignation, was essentially a failure of the Roman republic to sustain unity, as well as a failure of Roman citizenship, robbed by its rigidities of inner spirit. Rome’s prosperous era lasted only about 200 years. The United States had reached the same milestone when Richard Nixon fell.

*

Click the share button below to email/forward this article. Follow us on Instagram and X and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost Global Research articles with proper attribution.

Greg Guma is a Vermont writer, former editor, and author of 15 books, including Managing Chaos: Adventures in Alternative Media. Visit the author’s blog. He is a regular contributor to Global Research.

All images in this article are from the author

Global Research is a reader-funded media. We do not accept any funding from corporations or governments. Help us stay afloat. Click the image below to make a one-time or recurring donation.

.png) 1 month_ago

20

1 month_ago

20

French (CA)

French (CA)